What is most exciting about the world of nature’s pigments is you never know when you are going to discover something new. Veronica Bishop, my tech consultant, recently forwarded an article about such a color heretofore unknown to me. Thanks to her, I now have another pigment for possible inclusion onto my own historical palette, Han Purple.

Now, technically this is not a natural pigment but it is certainly a historical one. It is classified as synthetic, man-made by the Chinese during the Western Zhou period, 1045-771 BCE. It is still available today but I could not find any information on how widely used it is. The only natural blue available to the Chinese was azurite, and they had no purple.

Courtesy Creative Commons

So they invented one!

Azurite often leans more to the greenish side of blue, which means it is very difficult to simply add red and make a pleasing purplish hue. The only solution is to create something from scratch. In this instance, without getting too technical, heating a mixture of barium mineral, quartz, a copper mineral, and a lead salt will result in both a purple and a blue pigment.

It is speculated that this is a similar technique used by Ancient Egyptians to make their workhorse pigment, Egyptian blue frit. You may recall this from my Lessons from the Pharaoh’s Tomb stories. By switching calcium with barium mineral, the alchemists in Egypt created a surprisingly beautiful and versatile blue pigment. The pigment was used widely to decorate artworks of all kinds throughout the Ancient Egypt period.

Egyptian Blue Frit used in the vase.

Painting an Army with Han Purple

Similarly, and even more interesting than the formula for the making of Han Purple is how the Chinese used the pigment for the decoration of their artforms. Looking back to 1985 when I traveled to China and first set eyes on the newly-discovered Terracotta Warriors, I had no notion of what pigments were used to adorn the figures. It is now known that Han purple was used widely to paint the armies of men, horses, chariots, and weapons, all throughout the staggering numbers, over 8,000 in total, all handmade and hand-painted clay artifacts.

Beautifying an Afterlife with Pigment

The Terracotta Warriors, discovered in 1974 by a farmer on his land in Xian, China, is a legion of sculptures representing the army of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, 259-210 BCE. This funerary art was buried with the emperor in 210-209 BCE. You can only imagine the incalculable amounts of paint, which of course included Han purple and blue, and other materials that were needed to cover the surface of clay objects, not considering the infinite numbers of painters too. All this to protect the emperor in his afterlife.

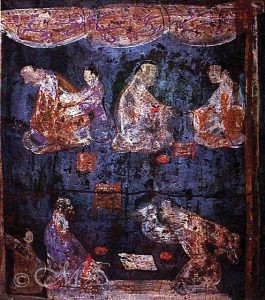

Because of the expense of producing the Han pigment, evidence shows it likely was used to show status and used mostly on the trousers of the warriors. A cheaper natural azurite was employed for those of lower importance. Much like the Ancient Egyptians used their Egyptian blue, the Chinese used Han purple for many other purposes and decorations on beads, pottery, vases, figurines, wall paintings, tombs, funerary objects, textiles, metal objects, and murals.

Supply Demands the Use of a Royal Pigment

Throughout history, shades of purple, violet, and red have been held in high esteem. In certain cultures, these colors were reserved solely for royalty, religious figures, and the aristocracy. Common people were forbidden to wear them. Perhaps the reasoning for this relates specifically to the prohibitively high cost, which simply implies out of reach for most people. Supply and demand played an important role also.

Today, there are suppliers such as M. Graham, Winsor Newton, Michael Harding and so many more making endless shades of purples and reds from the deep smoldering dioxazine to the subtle pinks. Some are available in pearlescent too.

Calm the Numbers and Become Liberated

Someday after the pandemic, wander through Michael’s art section for a while, and you will be dazzled or overwhelmed depending on your temperament. In so many ways, sticking with a handful of tried and true natural pigments can be liberating. But still, the stories about the origins of pigments used since prehistoric times are endlessly enlightening. If you ever run across something new like Veronica, please send it my way.

Hi Margret,

I wanted to tell you how much I have enjoyed your blogs, research and sharing all these years! As a sculptor, I don’t often use pigmented color as much as I’d like, it is fascinating and so much appreciate you carrying on the traditions and knowledge.

It was my good fortune to meet you years ago at breakfast during our previous AWA show at the Booth Museum, and delighted that you are now part of Salmagundi, so appropriate given your talents and interests.

Stay well and keep up the inspiration!

Hi Cathy, How lovely to hear from you and to know you are enjoying my blog stories. It is quite fun doing the research. I think I am a pigment nerd! I certainly do remember meeting you at the Booth Museum, a beautiful exhibit and venue. It is a total honor to be a member of the Salmagundi, since 1998. Dave and I went to an exhibit there in 2015 for the OPA Virtuosos Exhibit. I was in awe of the ambiance and history of the club and those who ‘came before’. Hope your sculpture is going well. Stay safe till we can get through these challenging times.